The idea of addressing “gun violence” as a public health problem persists among a number of scientists whom I think should know better: many of my fellow physicians, led by some of our specialty organizations. Guns are not pathogens—it is how they are used that matters.

Epidemics are not characterized by gradual steady declines in morbidity and mortality, as homicides and violent crime have shown, accompanied by dramatic increases in gun ownership for 20 years.

Their campaign is especially disingenuous as we find that our own health care professions are responsible for as many as 400,000 deaths and 10-20 times as much serious harm to patients every year.

Yes, over 30,000 Americans die yearly in shootings. About two thirds of those, suicides, can properly be considered health issues, because they almost always involve serious mental illness. Almost all the rest are homicides, which are criminal matters. The smattering of accidental shooting deaths, 505 in 2013, are from negligence or carelessness. Beginning with its seminal papers, much of existing “‘public health” firearms research is biased and poorly designed.

Comparing American shooting deaths to other developed countries’ raw numbers is another mistake. Homicides and violent crime, even with guns, can increase after a country confiscates citizens’ firearms. If one excludes murders in our gang- and drug-infested, poverty stricken urban areas, the United States has very low levels of violent crime and homicide. This is even more remarkable because we have the highest rate of civilian gun ownership in the world. Considering that, the United States is among the safest places to live in the world.

But poor urban minority youth with little hope in their futures find identity in gangs, get pulled into drug addiction or dealing, and comprise the largest numbers of both perpetrators and victims of shootings. Individuals’ networks and associations highly correlate with risks of violence, and suggest potentially effective ways to intervene preventively. Examples have included Richmond, Virginia’s Project Exile and Cure Violence (formerly Ceasefire—Chicago) in Illinois. Variations in gun laws and rates of violent crime among cities and states also point strongly to interpersonal, cultural and economic factors affecting rates of violence (compare violent crime and shootings in Chicago, the District of Columbia, Los Angeles and New Orleans with, say, Vermont, Utah and New Hampshire).

Equating motor vehicles and traffic deaths with firearms and shooting deaths distorts reality—apples are not oranges, no matter if they are the same number. Traffic deaths are almost all accidental, involving human error. Shooting deaths, by contrast, are almost all intentional. Accidental deaths with firearms totaled only 505 in 2013. Both gun accidents and homicides have been declining nationwide, even while the number of firearms in America has dramatically increased. We are far safer from accidental harm from our guns than our cars when they’re operated correctly. So don’t shoot while intoxicated or texting.

Health researchers rarely acknowledge any benefit of firearms. But the National Research Council estimated that there are between 500,000 and 3 million instances of active self-defense using firearms against crime and assault.

Too many overstate the role that mental illnesses play in the commission of violence, including violence done with guns. While most mass murderers of strangers probably have some, usually untreated, mental illness contributing to their acts, these events are extremely rare. The truth is that people with mental illness are no more likely to cause violence and much more likely to become victims than those in the general population.

Suicide is the issue when it comes to the impact of mental illness on firearm deaths: gun suicides have somewhat increased since 1999, but have declined as a proportion of all suicides. The immediate availability of a gun is a serious risk for someone with suicidal ideas. But as with homicide, we have to compare cultures to understand the deeper patterns of suicide.

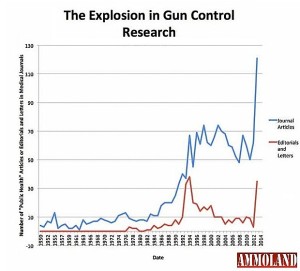

Despite health researchers’ complaints, the number of “gun violence” studies published in medical journals has really increased although, as the field of medicine keeps growing, their proportion has lessened. Considering the related literature in criminology and economics, which health researchers largely ignore, there is actually more research than ever. Private funding of (anti-)gun research keeps increasing as has its underwriting of more political activism for gun control. Still, organized medicine wants more government funding of public health research into the causes and cures of “gun violence”. Academics in every subject always want more money to support their work and to grow their fields.

Despite health researchers’ complaints, the number of “gun violence” studies published in medical journals has really increased although, as the field of medicine keeps growing, their proportion has lessened. Considering the related literature in criminology and economics, which health researchers largely ignore, there is actually more research than ever. Private funding of (anti-)gun research keeps increasing as has its underwriting of more political activism for gun control. Still, organized medicine wants more government funding of public health research into the causes and cures of “gun violence”. Academics in every subject always want more money to support their work and to grow their fields.

The fact is, there is no limitation on the Centers for Disease Control to perform or fund such research. In 1996, Congress simply insisted that the CDC shall not use its public funding to advocate for gun control. Banning civilian firearms was the CDC leadership’s expressed agenda. Congress never restricted the CDC or other agencies from performing research into gun injuries and deaths. (The relevant text: “none of the funds made available for injury prevention and control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention may be used to advocate or promote gun control.”)

In fact, when Wilmington, Delaware asked the CDC for help to analyze the causes of its exploding homicide rate, the CDC did its job. It analyzed the city’s gun crime problem and made serious recommendations about addressing the underlying risks that draw people into it, rather than exploring further ineffective gun control measures.

There has been a great deal of noise and very little substance over the years by anti-gun medical, political and bureaucratic parties. The latest, delivering a petition to Congress from 2,000 physicians to remove those non-existent “funding restrictions for gun-violence research” is underwhelming. That is only 0.2% of the physicians in our country. There are many more than that among the millions of supporters of gun rights organizations, represented in part by Doctors for Responsible Gun Ownership.

— DRGO editor Robert B. Young, MD is a psychiatrist practicing in Pittsford, NY, an associate clinical professor at the University of Rochester School of Medicine, and a Distinguished Life Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association.

All DRGO articles by Robert B. Young, MD.

[Editor’s Note: This article was originally written for National Journal, at the request of Larry Keane of the National Shooting Sports Federation, in response to the December 28, 2015 article: The Smartest Way to Address Gun Violence? Research, which called for more funding for public health research about “gun violence”. Upon the acquisition of National Journal by The Atlantic, this article was not published.]