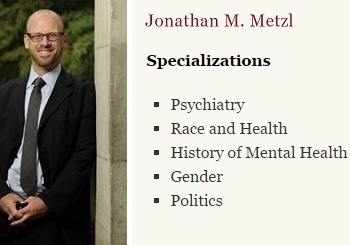

The discussion continues within health care and the law about what to do in cases of suspected dangerousness in possibly mentally ill people. Balancing individual civil rights to liberty (including gun possession) with trying to ensure public safety will always be imprecise. A review on March 25 in Psychiatric Times by Jonathan Metzl, MD, PhD, “Gun Violence, Stigma, and Mental Illness: Clinical Implications” fairly describes current thinking on the subject in my medical specialty of psychiatry, both in defining the limits of effective mental health intervention and showing the social engineering bias of many academics.

(Be sure to read my colleague, Dr. Timothy Wheeler’s piece “Slander as Science” regarding Metzl’s December article on mental illness and mass shootings.)

Metzl sets out “4 central assumptions that underlie many US political and popular associations between gun violence and mental illness:

• That mental illness causes gun violence

• That psychiatric diagnosis can predict gun crime before it happens

• That US mass shootings teach us to fear mentally ill loners

• That because of the complex psychiatric histories of mass shooters, gun control “won’t prevent” another Tucson, Aurora, Newtown, or Navy Yard.”

It is a thorough discussion, boiling down to the answers: rarely, not, wrongly, and true:

First, just having some mental illness, which includes an extraordinarily wide spectrum of disorders, in no way determines one’s risk of doing violence short of announced intention which, as in the case of James Holmes in Aurora, Colorado, needs to be taken seriously by all concerned. Drug abuse, for reasons involving impulse control, addictive drive and the illegality of most drugs of abuse, does generally increase those risks.

Second, as Metzl rightly puts it, “Data that support the predictive value of psychiatric diagnosis in matters of gun violence are thin at best. … Psychiatric diagnosis is in and of itself not predictive of violence, and the overwhelming majority of psychiatric patients do not commit crimes.” Even schizophrenia, with or without paranoia, does not make violence likely—in fact, to the contrary, anyone with mental illness is more likely to become victimized by violence. And neither psychiatrists nor anyone else are able to predict violent behavior consistently and reliably.

Third, many people with mental illnesses are lonely partly because of their symptoms but also because of the stigma of their differences from others. But again very, very few of them are at any risk of harming someone.

Unfortunately, Metzl then veers into a disquisition on the changing racial and associational assumptions society has seemed (to him at least) to make regarding the profiles of troubled and violent individuals. It is true that in the 1960s and 1970s part of the impetus for gun control was white society’s fear of armed African-Americans (e.g., “Black Power” waged aggressively). I’m not convinced that society’s picture of the greatest threat is now “the mentally disturbed, gun-obsessed, white male loner”. There are enough well-known exceptions to that rule (Seung-Hui Cho at Virginia Tech, Aaron Alexis at the Washington Navy Yard and Nidal Hasan then Ivan Lopez at Fort Hood) that it’s harder to justify that as a general cultural impression than as Metzl’s own perception.

Fourth, he acknowledges that neither universal background checks nor more alert mental health professionals could likely have prevented or would prevent any mass shootings. They are too rare in the overall numbers of violent crime, which is far more a problem of “everyday violence [that] disproportionally affects lower-income areas and communities of color”.

But Metzl (a sociologist and psychiatrist) leaves science behind when he says that the solution is, yet again, “investing more resources to support social and economic infrastructures and support systems”. He goes further astray by suggesting that mental health expertise could enhance understanding of “[c]onnections between loaded handguns and alcohol; the mental health effects of gun violence in low-income communities; or the relationships between gun violence and family, social, or socioeconomic net- works[sic]” and “the complex anxieties, social and economic formations, and blind assumptions that make people fear each other in the first place”, as if ‘gun violence’ is something very different from other lethal violence. Suggesting that psychiatry “could help society interrogate what guns mean to everyday people, and why people feel they need guns or reject guns” raises other concerns about where physician inquiries about gun ownership can lead.

Psychiatrists treat mental illness, which is a very rare cause of violence. One shouldn’t be afraid of the mentally ill; they deserve compassion. Psychiatrists aren’t mind readers and can’t predict the future, or the effect of impulses that may arise in people. We do have a good understanding of individual human psychology and neurobiology. When we aren’t diverted by our urges toward complicated analysis and societal engineering, we also recognize that violence is mostly a very bad choice by the perpetrator.

Intervening in situations where someone’s mental illness might make them destructive is a good thing for society and, if it is done with clear due process and results in good treatment, for the ill person. That strengthens individual rights by restoring capacity to deal with reality to someone who is impaired. But we still have to help ourselves when violence is threatened, whatever our theories about why it happens. That’s the part of the equation missing from most health care approaches to ‘gun violence’.

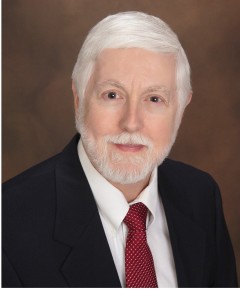

— DRGO editor Robert B. Young, MD is a psychiatrist practicing in Pittsford, NY, an associate clinical professor at the University of Rochester School of Medicine, and a Distinguished Life Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association.

All DRGO articles by Robert B. Young, MD.