We haven’t reviewed much research lately, which is DRGO’s raison d’être. So let’s take a look at a study presented in October at the American College of Surgeons’ annual meeting’s Scientific Forum. “Stand Your Ground: Policy and Trends in Firearm-Related Justifiable Homicide and Homicide in the US” by Marc Levy et al tries to show whether the spread of Stand Your Ground laws has increased even non-justified firearm homicides.

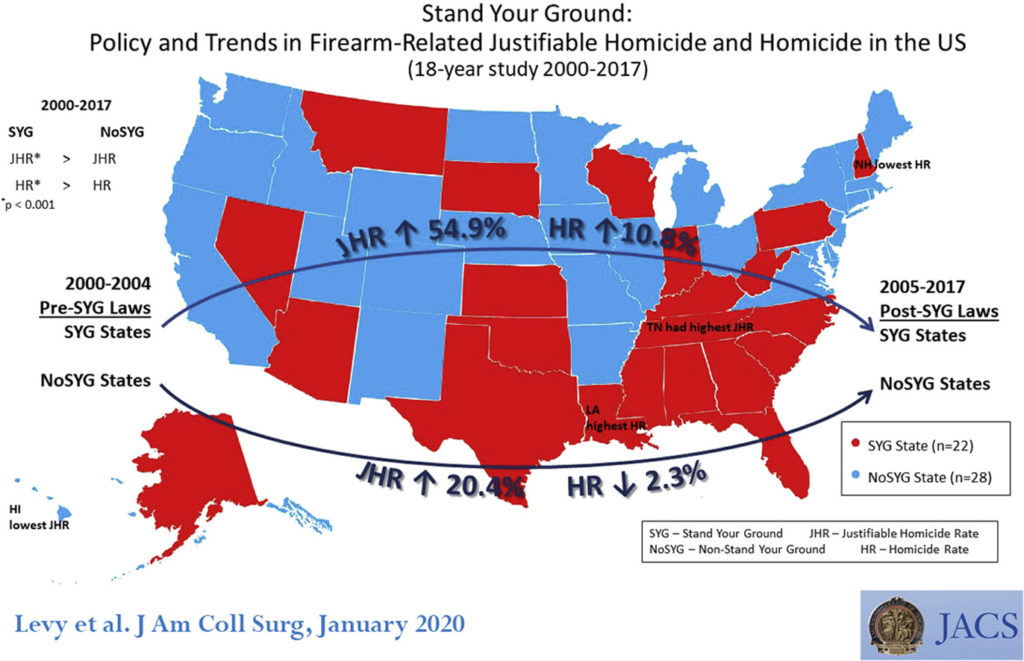

The study methods seem superficially sound. The authors collected national statistics for each year from 2000 to 2017 from several government databases, and compared rates of justified firearm homicides (JHR) versus other firearm homicides (HR, excluding law enforcement actions) before and after enactment of SYG laws. 22 states became SYG states during the study period (from 2005 on, Florida first and from 2006-2011, the other 21 did). 28 remained non-SYG states. Because Missouri, Idaho & Utah enacted SYG statutes only 2017-18, they were considered part of the 28 non-SYG states.

Their conclusions broadly suggest problematic increases in both JHR and HR after SYG laws were introduced across all 22 states.

However, there are quite a few problems with their methods and analysis. In no particular order:

- SYG is a rarely used defense, and JH is documented far more rarely than it is ultimately found. Statistics reflect only the first assumptions of police and prosecutors. Many JHs begin as homicide investigations that conclude, days or (if tried) months or years later with findings of JH. This inescapable under counting is an inherent major flaw in any study on JHR.

- It does not appear that they correlated their findings on firearm homicides with overall homicide, violent crime and property crime rates. Part of the intent of freeing citizens to defend themselves anywhere is to reduce all those crimes, not just firearm-related ones. Because we know felons don’t want to be shot, and avoid suspected armed victims; this is a substantial rationale to the SYG idea, following up the Castle doctrine.

- They point out that they did not attempt to correlate their findings with any other factors, such as “Other policies enacted in states during the period of this study [as well as] . . . State poverty levels, population diversity, and firearm ownership.” Not to mention varying law enforcement practices, educational and political differences, ethnic disparities, etc. What about baseline crime rates? How about differences in law enforcement and prosecutorial attitudes toward self-defense outside the home, even if the state is non-SYG?

- DRGO readers know that one of our biggest complaints about public health research into violence is the snapshot (or “case study”) approach comparing different places at a given time. This one is better, in that they report what happened before and after establishment of SYG laws in each state, which serve as their own controls. However, that is not the same as examining changes in trends before and after. An increased rate could actually be an amelioration of more rapid increase before; a decreased rate could be negative if the prior rate had been decreasing more slowly. Unless this is defined, overall changes in rates at a given point do not tell the whole story.

Examples of these problems can be seen in their data about New Hampshire, Alabama and Louisiana. New Hampshire had the lowest HR before and after its SYG law while Louisiana (New Orleans) had the highest HR overall. Neighboring Alabama categorized only two homicides as justified from 2009 to 2017 following its SYG enactment in 2008, despite reporting many more previously. SYG Tennessee reported the highest JHR all through the study, non-SYG Hawaii had the lowest. Nor do we yet know the way rates may change in Missouri, Idaho and Utah. And aside from Pennsylvania, with the Philadelphia metro area, all the SYG states are consistently rural.

Overall, JHR rose about 55% in SYG states over the study period, while HR rose about 11%. Meanwhile, JHR rose about 20% in non-SYG states with HR dropping about 2%. Because legally determined JH is still very rare, they cannot offset increases in HR. But any increase in JHR should be applauded.

They conclude, along with a number of predecessors on this topic, that SYG laws are a risk to public health that should not be adopted and should be removed where they have been instituted. But studies like this are riddled with inconsistent data collection and unanswered questions. They end up only echoing the pre-existing opinions of researchers who add one more low-quality paper to their résumés and to the rampant anti-gun, pro-control academic ethos.

The cultural factors that drive violence and are different in different places were simply ignored. Culture and psychology are the main determinants of propensity to violence, not the means. Ignoring this is the greatest fault of their and virtually all such work.

.

.

— DRGO Editor Robert B. Young, MD is a psychiatrist practicing in Pittsford, NY, an associate clinical professor at the University of Rochester School of Medicine, and a Distinguished Life Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association.