[This is the second of a two part series. Part 1 is here.]

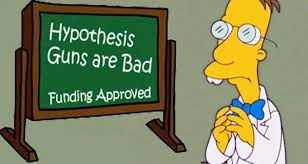

Next comes the gem of the whole issue, “Testing the Immunity of the Firearm Industry to Tort Litigation” by three authors affiliated with Stanford’s Law and Medical Schools. It is straightforward legal thinking about how to find the “chink[s] in the legal armor that shields the firearm industry from tort liability.” Why? “For the gun control advocates who helped orchestrate many of the cases, such destabilization was a central goal.”

This is not research, not scientific inquiry, nothing that has any place in a supposedly objective medical journal. This is blatantly anti-gun, discussing how to blame and bankrupt the domestic firearms industry based on liabilities not recognized for any other, which were hopefully proscribed in 2005 by the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Firearms Act.

It’s an unambiguous statement of opposition to the lawful manufacture and distribution of firearms in the United States and therefore of the goal to eliminate private ownership of firearms. The Journal’s and the contributors’ anti-gun purpose is made perfectly clear by the inclusion of this wholly goal-oriented, non-medical tactical planning.

***********************************

“Temporary Transfer of Firearms From the Home to Prevent Suicide” comes from John Vernick, JD, MPH (et al) of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore. It spends a lot of words to point out one major problem with “universal background checks”. If a suicidal emergency demands that firearms be placed for safekeeping with a trusted friend, it can’t easily be done. Legal requirements for checks at a NICS terminal of the recipient make this too inefficient. The authors don’t compare this to the equally critical task of removing weapons from someone dangerous to others, but there is more opportunity there for law enforcement to intervene. In neither case is due process adequate anywhere, which these authors do not address. (That is not often recognized by institutions promoting gun seizure.)

***********************************

Next, another original work, “Firearm Laws and Firearm Homicides: A Systematic Review” by Lois Lee, MD, MPH of Boston Children’s Hospital, et al (including Eric Fleegler, MD, MPH of the same). They purport to show “that stronger firearm laws are associated with reductions in firearm homicide rates . . . [and that the] strongest evidence is for laws that strengthen background checks and that require a permit to purchase a firearm.” This is part of continuing attempts by anti-gun academics to make the case that restrictive gun laws diminish “gun violence” (as always, ignoring effects on violent crime generally). Funding came from The Joyce Foundation via David Hemenway, PhD of the Harvard School of Public Health.

To their credit, they admit that the “effect of many of the other specific types of laws is uncertain, specifically laws to curb gun trafficking, improve child safety, ban “military-style assault weapons”, and “restrict firearms in public places.” That is, these make no one safer.

This is not original research. It is a meta-analysis, that is, an examination of many examples of previous work. That can lend a sense of trends in findings, but can’t be relied upon for definitive conclusions. Each of the 34 studies (of 582 on the subject) published from 1970 to 2016 that met their criteria were done by different people with different study designs and methods, and different approaches to statistical analysis. So their findings cannot be summed into an overall conclusion. In their own words “The methodologic limitations of the studies restrict the robustness of some of the reported results.”

The authors searched medical/public health (13 authors), criminology (8), legal (3) and sociology (3) peer-reviewed sources; they did not very thoroughly search the economics (2) and political science (1) literature. They ignored anything not peer reviewed (and so missed Kates & Mauser’s Would Banning Firearms Reduce Murder and Suicide?). They have Kleck & Patterson’s The Impact of Gun and Gun Ownership Levels on Violence Rates, 1993, but no more from Kleck. They have Lott & Mustard’s 1997 paper Crime, Deterrence, and Right-to-Carry Concealed Handguns, and nothing from economist John Lott since. As the preeminent investigator of the relationship of firearms and violence, that disqualifies this paper as a serious study. But there’s plenty from the usual echo chamber denizens: Hemenway, Webster, Wintemute, Kellermann, Rivara, Fleegler, Ludwig, Cook, The Brady Campaign, etc.

The authors note that in “2004 and 2005, two comprehensive reviews of US firearm legislation conducted by the Task Force on Community Preventive Services, an independent, non-federal organization working with the US Department of Health and Human Services, and the National Academy of Sciences concluded that the published evidence was insufficient to determine the effectiveness of any specific type of firearm legislation, either independently or in combination with other laws.” So consider that breadth of inquiry against these Harvard staff who assume that a “public health approach can decrease firearm homicides and injuries” and keep producing work that calls for more funding for work like theirs.

The section that argues for “permit to purchase” requirements reducing firearm homicide rates lays aside two older studies with negative findings and relies only on more recent ones looking at Missouri and Connecticut before and after their laws changed. In these, however, the investigators cherry-picked data and ignored longer-term trends in Missouri, and chose inappropriate controls for Connecticut that void those conclusions. These have been definitively debunked for those outright deceptions.

Among the four papers on which they base their conclusion that stronger background checks reduce firearm homicide, one is from 2016 in Lancet by Kalesan et al, which DRGO and others have found to be laughable. A second one is from 2005, or contemporary to the earlier high-quality reviews that found no such effects. A third is labeled by the author as “exploratory”, so not claiming the confidence of the current reviewers. Perhaps that is enough to question their choices. From another point of view, certainly more accurate NICS checks with more complete reporting from states of the basic prohibiting factors would help. NICS produces over 94% false positives based on incomplete data; only about half of states even yet statutorily require complete information submission to the NICS.

Far the most interesting thing about this paper is that, even with their credulous and hopeful perspective, they had to conclude that the vast majority of legislation has not been shown effective in reducing firearms homicides. These include the categories and interventions as follows:

- Curbing Firearm Trafficking:

- Gun dealer regulations

- Limiting bulk purchases

- Banning sales of certain guns

- Minimum and mandatory sentencing for crimes with firearms;

- Strengthening Background Checks:

- the Brady Act established background checks;

- Improve Child Safety:

- Safe storage laws

- Juvenile age restrictions;

- Banning “Military Assault-Style Weapons”

- Restricting Firearms in Public Places:

- Right to concealed carry

- Presence of guns in public places (including gun-free zones)

Despite Lee & Company’s belief “that stronger firearm laws are associated with reductions in firearm homicide rates”, their proud trumpeting that “laws that strengthen background checks and that require a permit to purchase a firearm” make some difference, the underlying, unstated result is that even their flawed approach found that 10 other actions can’t be supported. We appreciate their help.

***********************************

Last, we see a Research Letter, “Trends in Research Publications About Gun Violence in the United States, 1960 to 2014” by Ted Alcorn, MPH, MA of Everytown for Gun Safety, that noted academic resource. He had his research assistants review, to some extent, 10,347 articles and culled them on the bases of relevance, completeness, presence of an abstract, etc. to 2,207. He found that publications “increased markedly” from 1985 through 1999, then stayed around 90 annually through 2012. Since then they have increased further to 165 in 2014.

He acknowledges that he could not “provide . . . a complete account of the scientific literature” on this subject . . . and neither the quality nor the scientific significance of individual studies was assessed.” He is also concerned that there are “still few active career researchers.” One could draw inferences about a potential career researcher &/or activist in a subject bemoaning the lack of work and researchers in his area.

We addressed this point earlier: there is more work than ever being done on “gun violence” and little of it good, as these reviews show. In fact, there is a remarkable amount going on, given the accelerating growth of medical knowledge and the consequent demand for significant basic and clinical research to be done about true medical and public health problems.

What else to conclude? There are lots of academics and activists, richly funded by anti-gun wealth directly or via their organizations and departments. Yet they still complain that there are not enough of them or enough grants supporting their work. Contrast this with the virtual absence of funding for research to understand the societal (and individual) value of responsible gun ownership and use.

***********************************

To the pro-rights side’s advantage, there is plenty of evidence for the benefits of firearms in America, coming even from those who can’t see that, like much of what we looked at here.

With so much more evidence from experts (as well as DRGO’s) who recognize the value of supporting the right to keep and bear arms, our job is simple.

We just follow the facts where they lead.

— DRGO Editor Robert B. Young, MD is a psychiatrist practicing in Pittsford, NY, an associate clinical professor at the University of Rochester School of Medicine, and a Distinguished Life Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association.

All DRGO articles by Robert B. Young, MD.

[This article was written with assistance from the DRGO Publications Review team.]