Gianni Pirrelli, PhD is a licensed New Jersey clinical psychologist and a friend of DRGO. He has shown sympathy for folks whose firearms have been confiscated and are trying to convince government that they are actually safe and responsible and deserve them to be returned.

The subject for Dr. Pirelli and his co-author Philip Witt, PhD, a forensic psychologist, in this new paper is the culture of firearms ownership. It was just published in the Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research in July.

Dr. Pirelli forwarded it to us and was willing for us to see it shared with our readers. We can’t show the original, since it is (as are too many) behind a paywall, but we hope this freely quoted review will present it fairly and usefully.

They advocate that mental health professionals recognize the validity of the ways in which people have guns in their lives. The more general point this arises from is that people should be aware of “subcultures . . . and avoid grouping individuals according to one . . . cultural identity because doing so would neglect important differences at the individual level.”

The problem is that “Professionals can have preconceived perceptions and social preferences that impact interpersonal interactions. . . [This] ethnocentrism . . . is the tendency to view one’s personal norms as appropriate and others as deviant.” This blindness is endemic among anti-gun researchers and writers—if they don’t like guns, then liking them must be deviant.

Our interests in having and using firearms are varied: “In addition to the military, firearms are present in various other contexts, such as law enforcement and corrections as well as among civilians.” And there are a lot of us: “…one in three households has a firearm and there are over 300 million firearms in the USA.”

Contradicting the liberal-media stereotypes, “The many firearms in this country are used for a variety of reasons, most of which are not related to violence or suicide, despite the fact that many people have developed negative associations with firearms (e.g. mass shootings, school shootings). However, with 300 million firearms in the USA… it is safe to say that most are not implicated in acts of violence or suicide.”

“Firearms hold important cultural significance to some people, and the prevalence and profile of firearm-supporting subcultures are often overlooked.” Sport shooting is consistently ignored by the general public and media. A crystal-clear example is Kim Rhode. She “became the first Olympian to win a medal on five different continents and the first Summer Olympian to win an individual medal at six consecutive summer games. . . a feat that no other female Olympian (and all but one male Olympian) in history throughout the world has ever accomplished.”

“Given one-third of the US population owns firearms and an even greater number has either interacted with or has been exposed to them at some level (e.g. shooting ranges, family members who own firearms or who have are military, law enforcement, correctional, or security personnel), practitioners will likely work with someone from this subgroup at some level and, perhaps, even need to address a firearm-related matter directly.”

The authors point out that mental health professionals are more likely to encounter clients with these experiences than to have them themselves, so that few are prepared to be able to envision the world from the that point of view. One major problem with this is that practitioners, properly concerned with risk of harm, too often equate possession of firearms with risk of using them, and may report clients to authorities for intervention too readily. Training to discriminate between these factors is simply not part of learning to do mental health risk assessment.

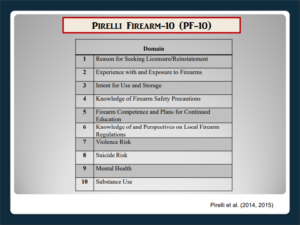

Similar problems exist when professionals are asked to attest to clients’ fitness to resume possession of their firearms. That is a bridge too far for many practitioners, which leaves too many confiscations in limbo. It is noteworthy that Pirelli with other colleagues developed a 10-point guide for practitioners to reference as they do such assessments, which may make these more accessible as it becomes better known. (See the Pirelli Firearm-10 [PF-10]).

Another confounding preconception occurs with political views, in which more conservative ones tend to correlate with stronger pro-gun and gun rights beliefs and more progressive ones with less experience of guns and more support for gun control policies. “[M]ental health professionals are . . . more likely to espouse liberal than conservative [politics]”, so “their objectivity may well be impaired in professionally addressing firearms-related issues.”

In more detail, the authors describe 7 sub-groups of gun-concerned groups, across the political and legal spectrum, each having its own perspective with which forensic practitioners in particular must be able to understand:

- 2A groups

- Shooting sport groups

- Rod & gun and hunting clubs, and shooting ranges

- Gun control, gun violence prevention, and anti-gun groups

- Military, law enforcement, and corrections

- Criminals (gangs, organized crime, et al)

- Victims of firearm-related suicide or violence (including domestic violence)

People’s ideas by be influenced by such experiences, or from exposure to others who have.

The obvious conclusion is that “mental health professionals will be more effective at providing professional services if formally educated on firearms and firearm-related issues. . . .[and] must develop cultural competence associated with the . . . populations we have outlined.” This leads to their recommendations that practitioners who are likely to work with people who have possibly divergent opinions and experiences of firearms need to educate themselves about all aspects of these potentially foreign attitudes. That should not only include familiarization with literature about guns in society (both pro- and -con) but also hands-on safety and shooting training with firearms.

It’s good news that Pirelli and colleagues plan to publish a textbook later this year that covers and fulfills these educational needs. It’s even better news that someone in health research takes seriously how normal firearm use is in America.

— DRGO Editor Robert B. Young, MD is a psychiatrist practicing in Pittsford, NY, an associate clinical professor at the University of Rochester School of Medicine, and a Distinguished Life Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association.