What if a cheap, reliable method of preventing a common but serious injury were available and ready for the market? As an ear surgeon who has seen hundreds of patients with irreversible noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL), I would welcome it with open arms.

Too many people in our noisy world have suffered irreversible hearing loss. Only after experiencing it do they learn how socially isolating this entirely preventable injury can be. Their family members also bear the burden of impaired communication, as many frustrated spouses can attest. The only effective treatment is hearing aids, a poor substitute for the intricate, ultimate-fidelity cochlea, the ear’s sound processor.

If such a useful hearing loss prevention method existed, shouldn’t the medical and public health world sing its praises and even promote it on its prominent media stage? Sadly, they wouldn’t if the injury-preventing device were a suppressor, the aftermarket firearm accessory commonly known as a silencer. The public health community has long opposed saving lives and preventing injuries if it involves the use of firearms. Their intransigence reflects similar prejudice in our gun laws regulating suppressors.

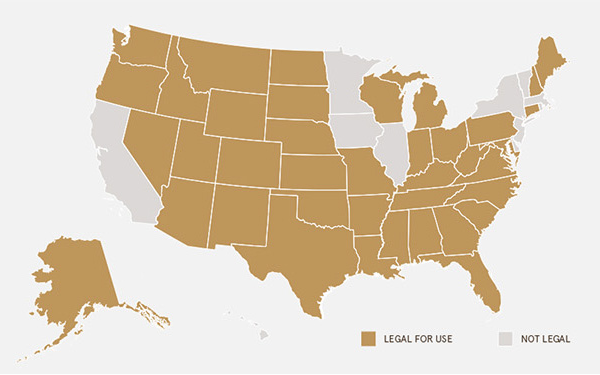

For starters the National Firearms Act requires the prospective owner of a suppressor to apply to the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF) for a revenue stamp at a cost of $200. The states then apply their own restrictions up to and including making ownership illegal.

Readers may be surprised, as I was, to learn that suppressors are legal in most states, with the usual holdouts being the freedom-snuffing suspects like California, New York and Illinois. Recent years have brought a mini-flurry of states relaxing bans on their use by average consumers—hunters and sport shooters—with Iowa and Maine being the latest to engage the issue. It’s a long overdue adoption of a logical consumer safety feature for firearms.

Suppressors are designed to diffuse the punishing sound energy of a cartridge firing from a gun—a sudden pulse of energy sufficient to injure or even kill the delicate hair cells of the inner ear. Although the bullet can still generate considerable impact noise after it exits the barrel if it travels at supersonic speed and causes a sonic “boom” or crack, its sound energy is reduced to a level that is much safer for the human ear.

Even a small .22 caliber round produces impact noise at a sound pressure level of around 160 decibels (dB), well above the limit considered safe by the Occupational Safety & Health Administration (OSHA). Larger caliber rounds in common use can produce 170 dB or more. A suppressor can reduce the measured impact noise by around 30 dB, which is the level of protection given by foam ear plugs or ear muffs.

Suppressors were invented in the early 20th century mostly as an effort to reduce noise pollution, a problem of growing concern then. One such innovation then for another popular and noisy consumer item was mufflers for auto engines. Suppressors were fairly uncontroversial until later in the century, when crime waves prompted corresponding waves of gun control legislation.

Most opponents of legalizing suppressors rely entirely on their knowledge of Hollywood bad guys screwing a silencer onto an ugly-looking black handgun, preparing for murder. They certainly don’t see on their big screens how hunters and their dogs can avoid hearing loss during the hunt, nor do they see junior shooting championship competitors being spared unnecessary permanent hearing loss in childhood. It has taken a determined educational campaign to counter the ridiculous caricature of suppressors that the public has adopted from watching TV and the movies. But it seems to be working, as understanding steadily replaces ignorance.

Opposition to the use of suppressors seems to align with opposition to gun ownership in general, with stated reasons ranging from simple ignorance to the embarrassing to the downright nasty.

In response to an Illinois bill to legalize the hearing-saving devices, Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart objected in this ABC News story on the grounds that gunfire noise in the neighborhood helps police more rapidly locate crime scenes. This is a shortsighted reaction on two counts. First, all crimes committed with guns are vastly outnumbered by lawful uses of guns. Illinois’s current ban on suppressors, even if Chicago criminals faithfully comply, needlessly exposes millions to ear-destroying noise, a social cost that is obviously prohibitive. Second, it’s doubtful that the residents of high-crime areas view the sound of gunshots as a neighborhood improvement.

One sign that proponents of suppressors are winning the public debate is the ramping-up of hostile rhetoric from opponents. The author of this Salon article trots out every rabble-rousing trick in the book to denounce the public’s growing adoption of suppressors—ritual condemnation of the NRA, the Newtown mass shooting, and even potty-mouthed name-calling.

We’ve heard this all before. When right-to-carry laws were sweeping the land one law enforcement officer after another voiced grave concerns, echoed by the media, that such laws would all but bring an end to civilized society.

When, in state after state, the dire predictions failed to materialize, most naysayers were pleasantly surprised, and they learned that regular citizens can be trusted with guns. They adjusted their attitudes accordingly. The same lesson is rapidly being absorbed by the public in regard to firearm suppressors—a valuable tool of public health prevention if there ever was one.

—Timothy Wheeler, MD is director of Doctors for Responsible Gun Ownership, a project of the Second Amendment Foundation.