Many of us want to teach our children about guns the right way—with appreciation for the good they can do in our individual lives and for what they mean to our nation. Teaching them about the harm they can do and how to avoid that is an even higher priority, so that firearms can serve and protect, not cause trauma being handled wrongly.

Good and usual recommendations include seeking out programs like Eddie Eagle from the National Rifle Association or Project ChildSafe from the National Shooting Sports Foundation. All good, but what if these aren’t available when it matters for your family?

True gun safety advocates don’t primarily delegate firearm instruction anyway. Raising kids to understand the value of firearms and how they should behave with them comes from the example of parents and other adults. Good citizenship, caring for the well-being of our fellows, is modeled by demonstrating responsible use of adult rights and privileges.

Examples like religious instruction, driver education and learning about appropriate sexual behavior come to mind. One can find numerous guides to talking and teaching about each of those subjects.

But where are the guides to talking to kids about guns?

Yehuda Remer found himself asking just that question, after becoming a gun owner in order to be better able to protect his family. He realized he couldn’t leave his family’s firearm education in the hands of Hollywood and other media and that, like in any family, the best education begins at home.

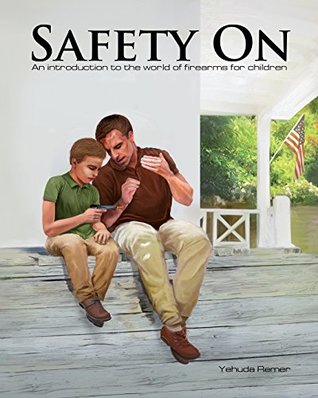

In the author’s words, Safety On “is meant . . . as an introduction to the world of firearms for children. Its goal is to plant the seeds of safe gun ownership into the minds of young patriots who will one day be responsible gun owners like the parents who teach them. It is up to the moms and dads of this country who exercise their 2nd Amendment rights to instill a deep respect for firearms. This book serves as a tool to open a dialogue between you and your child about keeping their ‘Safety On’.” Hear, hear!

The book is not written as a dialogue between parent and child. Rather, it portrays the thoughts of a boy Kyle, who wants to emulate his father and has been learning from him about gun ownership and use. The important rules of gun safety are conveyed conversationally with pictorial examples from Kyle’s life, as well as at the end with a list of the four familiar classic rules of gun safety.

Along the way, Kyle describes some of the habits his parents are inculcating. There is room for disagreement on this, but I especially like the expectation that he handle and care for his toy guns like his father does the real ones, never pointing them at people and putting them where smaller children cannot get at them. Developing these habits when mistakes can’t harm anyone makes them more reliable when they can mean life or death later.

Of course, the rules that all children need to know are here: “STOP! Don’t touch. Tell other kids not to touch. Walk away. Tell an adult right away.”

One page briefly shares some of the reasons that guns are important in society, largely for protection by and for good people but mentioning that they can be used in bad ways, too. That’s enough for most kids to know without getting into the gory details of criminal acts. It would also have been good to mention the fun shooting can be, including the rewards of competition like other individual and team sports children participate in.

The words “safe”, “safety” and “safely” are repeated throughout, a healthy redundancy. Another quibble relates to this, on the page describing how his father cleans, checks and stores his guns properly to avoid accidents. “Before my dad puts his guns away in his safe, he always double-checks that the safety is on. The safety makes sure the gun can’t fire or go off by accident.”

Of course, many firearms have no safety so this could cause confusion for those following too literally the book’s lessons. And it is ultimately the user following the Rules that ensures the gun won’t fire, purposely or accidentally, until the right moment—not a little lever. Introducing the concept of mechanical safeties leads down a road wisely not taken by the author toward explaining the many working parts of firearms. Those are subjects for an entirely different, larger and more advanced book.

But don’t let anything keep you away from this little gem. I warmly recommend it!

The level of writing is perfect for children who are old enough to begin learning about firearms but not old enough to use them independently. The illustrations are uncluttered and nicely reinforce the points being made, page by page. The principal characters are a bit vague ethnically, which is nice. We’ll look forward to the next volume portraying a daughter learning about firearms from her mother.

Remer recently published a coloring book that essentially replicates Safety On, but with line drawings instead of the color pictures that illustrate the main title. Kids may enjoy filling in the scenes themselves while getting an additional dose of the life lessons they contain.

To paraphrase founding father William Henry Lee, whose nobler quote resides prominently at the beginning of Remer’s book: “It is essential that Americans be taught how to use firearms when young.” Safety On, hopefully the first of a new category of firearm literature, can help you do that with your children. They will benefit, and you’ll be glad.

— DRGO Editor Robert B. Young, MD is a psychiatrist practicing in Pittsford, NY, an associate clinical professor at the University of Rochester School of Medicine, and a Distinguished Life Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association.