One of my older patients killed herself a few months ago. She had disabling chronic depression and other psychiatric issues, had abused medications and had overdosed dangerously several times, and felt unfulfilled and stressed at home. She was a delightful person for whom family was everything but always imagined she mattered less than she really did.

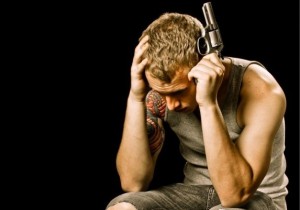

There was a handgun at home. I had addressed this with her and her family. They decided they would keep it locked up inaccessibly to her rather than remove it from the house. One day she was found dead of a self-inflicted gunshot. I’ll never know what precipitated that or how the gun came into her hand.

Suicide is the 10th most common cause of death among Americans. It is nearly always, as is said, a permanent solution to a temporary problem. Over 90% of the time, either already known or in retrospect, some treatable psychiatric illness is implicated. These deaths nearly always come as a shock, though many people are chronically at risk and may have attempted before.

And “means matter” as the meme reminds us. Having a firearm at hand significantly increases the likelihood of dying from a lethal plan or impulse. Shooting oneself (as well as jumping from high places) is more likely to be fatal than overdosing or hanging or cutting oneself.

Of the 32,000 or so Americans who die by gunshot each year, most are suicides. About half of all suicides are by gunshot. We often focus on murder and violent crime and the contribution of mental illness to them. The good news is that murder, violent crime and gun accidents have decreased year after year even as gun ownership increases. And the large number of people with psychiatric illnesses cause less violence and are at higher risk of becoming victims than the population overall.

But, perhaps surprisingly, the rate of death by shooting ourselves has increased in recent years. This reflects major mood and psychotic disorders, paranoia, and traumatic stress responses that are inherent in our biology but are inadequately treated. Drug abuse, youth and old age, physical illness, dementia and other problems raise the risks. This also reflects our culture, in which our fight is not yet won against the stigma of mental illness that keeps people from seeking treatment. Most murder-suicides, including mass murders, are probably an anger-laden subset since dying is usually their final intent.

For all the public attention to “death with dignity”, choosing death during terminal illnesses isn’t reflected in these numbers because it is usually a very private event. While such decisions reflect acceptance that people ultimately do have the right to die in their own way, many of these might not happen with better palliative care and depression treatment.

How do we reconcile this most frequent gun-related risk with our right to self-defense and to keep and bear arms? Like other harm caused with firearms, it won’t be solved by eliminating them, whatever the anti-gun faction dreams. So we need to recognize the signs of risk, long-term and immediate, and know how to respond. We need to use situational awareness on behalf of ourselves, families and friends to defend against suicide just like we do against assault.

When people are in distress and refer to hurting themselves or others, we have to try to get them help. They usually appreciate that. In unusual cases when someone denies any need for help or resists it, it takes more. Then we call 911, explain why we’re worried and police will come do their own assessment. If they concur, they’ll take the troubled person to a hospital for evaluation and possible admission.

Let’s not get distracted by the idea of means substitution. Cultures are different with different approaches (hanging in Mexico, drinking pesticide in El Salvador, jumping in Hong Kong—countries with few, strictly controlled civilian firearms). And people anywhere make different choices for many reasons: perceived comfort, post-mortem appearance or simply the examples of others.

It is difficult to know when someone suicides whether they would have done it in some other way. We obviously can’t use controlled study groups to test that hypothesis. A more important question is whether, when someone fails, they will repeat and ‘succeed’ later. If we prevent a death now from any cause, we give that person a longer life—potentially one in which suicide is not tried again if the right treatment is obtained.

We badly need stronger laws to commit people to psychiatric treatment when they cannot understand that need due to their illnesses. Too many people are on the street and in jails for lack of treatment opportunities. We need more mental health treatment resources in order to help them. The Cornyn/McSally, Murphy and Cassidy/Murphy bills pending in Congress could improve this.

‘Safe storage’ (which can’t effectively be mandated anyway) is not, when someone in the household is suicidal or homicidal. Removing them is best. So, along with ensuring treatment, laws permitting temporary custodianship of firearms are important to remove that too easy temptation when people are vulnerable.

This, like commitment to treatment, has to be done with strong protections for due process. That includes the opportunity to face the complainant, the right to legal counsel and the right of appeal. The term of such orders cannot be indefinite, and the process to return the property has to be in place and efficient. ‘Gun Violence Restraining Orders’ are an attempt to address this, but so far (e.g., in California’s) their due process protections for the accused are too limited.

The Cornyn/McSally bill better addresses this need and promotes more complete data submission to the NICS. However, it is hasty in routinely restoring gun rights on the day of discharge from a psychiatric facility. On leaving inpatient care (usually just a few days), outpatient treatment should continue for most. Their harm potential is reduced but may or may not have been eliminated.

Even psychiatrists can’t reliably predict more than transiently who will become dangerous, even with a very complete history and examining the individual. No one can keep someone from dying when they are determined to, because there are so many easy ways to accomplish that when it is one’s only goal.

Educating everyone about the risks of suicide is the main answer. It is especially important for those at most risk, the mentally ill, and it should be for everyone who owns the most immediately lethal tools for it, firearms. [Note: I am not talking about physicians telling patients what to do with their guns.] It is hopeful to see this beginning to happen at the point of sale, in Arizona and in Colorado at least.

Most people who attempt suicide (or violence, for that matter) show and tell someone, somehow, about their intent before acting. We all need to care about our loved ones and neighbors enough to take action to save lives as best we can.

— DRGO editor Robert B. Young, MD is a psychiatrist practicing in Pittsford, NY, an associate clinical professor at the University of Rochester School of Medicine, and a Distinguished Life Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association.