I n some thought-provoking discussion of the confluence of impulsive anger and gun possession, Jeffrey Swanson et al raise questions about the relevance of focusing on mental illnesses as risks in gun use.

n some thought-provoking discussion of the confluence of impulsive anger and gun possession, Jeffrey Swanson et al raise questions about the relevance of focusing on mental illnesses as risks in gun use.

They point out that there may be more validity in looking for signs of previous impulsive angry behavior in assessing risks of gun ownership. There is even some increased statistical risk of anger issues the more guns one owns.

So then (with a nod to Stephen Wenger), “Why aren’t the streets running with blood?” Because, as the authors note amid all their worry, “gun owners as a whole aren’t any more likely to suffer anger issues than non-gun owners. And the vast majorities[sic] of these people never have, and never will commit a gun crime.” Having 6 or more guns (which may correlate more with angry behaviors) may be because you’re a paranoid Travis Bickle, but it may also because you’re New Jersey antique gun collector Gordon Van Gilder (recently arrested for having a non-operational 18th century flintlock pistol).

They make good points about the need to identify people who are most likely to commit violence, and who should be kept from guns if possible. Using the “mental illness” label alone is lazy, discriminatory and ineffective. It is true that if we were able suddenly to “cure all serious mental illness in the United States, you’d only decrease violent crime by about 4 or 5 percent.” That means that keeping guns away from all these people isn’t at all justifiable, and wouldn’t substantially reduce violence rates. Depriving 100% of a class of people their rights in order to avoid the 5% who act badly just doesn’t sound right.

“Federal law already limits gun access for individuals convicted of a felony, and for people with misdemeanor domestic violence convictions. Swanson and his colleagues suggest … placing additional misdemeanors on the restriction list: assault, brandishing a weapon or making open threats, and especially DUI, given the well-documented nexus between problematic alcohol use and gun violence.” All this could make sense, if and only if there is full, costless due process required toward any temporary suspension of rights, and not a permanent one.

They point to other research showing that people with a single prior misdemeanor conviction are “nearly 5 times as likely as those with no prior criminal history to be charged with new offenses involving firearms or violence.” There are lots of kinds and degrees of misdemeanors. Only violent ones should be on the table, and it might take very wise parsing to distinguish, say, prank calls or trespassing from threatening harassment. Not everything that feels scary is dangerous.

There are wrong ways and right ways to restrict gun possession by demonstrably dangerous people without trampling on their rights to due process or on everyone’s constitutional rights. Mostly, we have to careful not to stereotype anyone, whether gun owners, people suffering mental illness, or even those who are just angry about something.

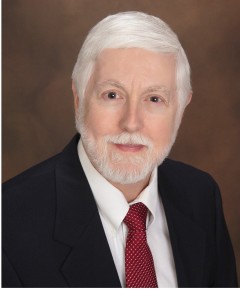

— DRGO editor Robert B. Young, MD is a psychiatrist practicing in Pittsford, NY, an associate clinical professor at the University of Rochester School of Medicine, and a Distinguished Life Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association.

All DRGO articles by Robert B. Young, MD.